Our world is full of sensory stimuli. Depending on what we see, smell, taste, feel, or hear, we are compelled to behave in a predictable way – like approaching tasty food or avoiding an oncoming car. The brain’s ability to make sense of the diverse sensory stimuli and to coordinate the appropriate behavioral response relies critically on the function of the cerebellum. This hindbrain region, critical to sensorimotor coordination, is conserved across vertebrates, from humans to birds to fish.

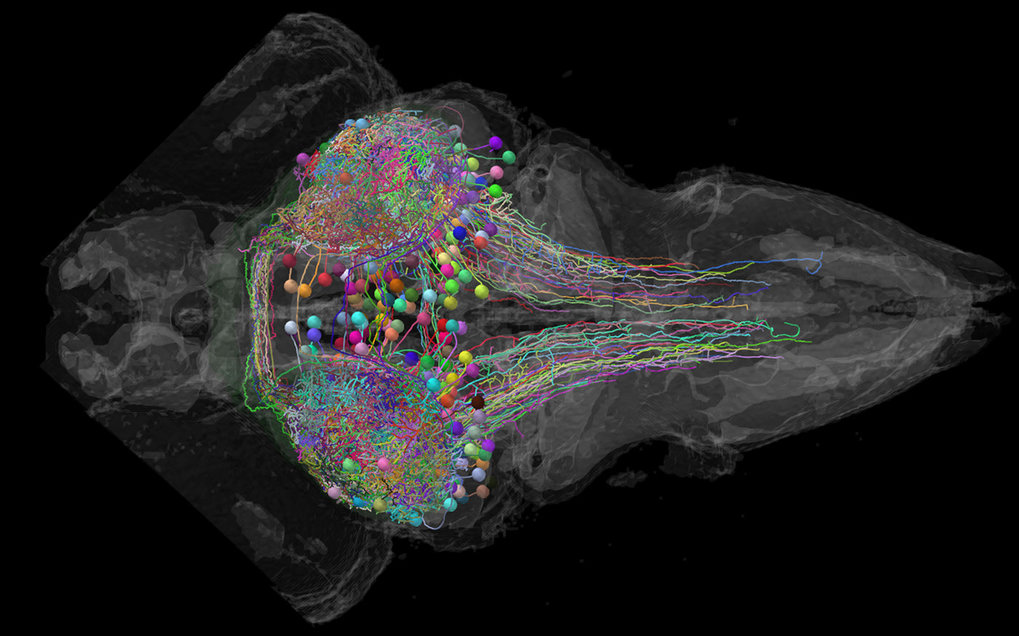

The mammalian cerebellum, however, contains hundreds of thousands of Purkinje cells, each receiving inputs from many thousands of presynaptic neurons. Cracking the cerebellar code here is nearly impossible, even with the latest methods. Ruben Portugues and his team thus focus on a "simpler" version: the cerebellum of six to eight day old zebrafish larvae.

“At this age, the zebrafish cerebellum contains about 500 Purkinje cells and is involved in behaviors such as swimming and eye movements”, explains Laura Knogler, who studied the cerebellar circuits together with graduate student Andreas Kist. “It’s all there and still very complex, but we have a chance to see all cells’ activity in the transparent brains of these fish and directly record the detailed activity of individual cells.” By studying the cerebellum of zebrafish larvae behaving within virtual-reality environments, the scientists were now able to tackle the central question of how the cerebellum coordinates behavior.

Like many vertebrates, zebrafish use visual cues to direct their movements, keep track of their environment or to identify potential predators or prey. Using this knowledge, the neuroscientists showed the fish different visual stimuli while observing neuronal activity and the motor functions. The surprising result was a cerebellar division into three behavioral modules, each encoding a distinct type of visual information: directional motion onset, rotational motion velocity, or changes in luminance. Every studied Purkinje cell belonged to one of these three modules.

In contrast, the behavior of the fish was encoded in nearly the same way by all cells. This became visible in an impressive way when the fish were swimming: “Nearly the entire cerebellum lit up with fluorescence, showing an overwhelming amount of Purkinje cell excitation during swim bouts”, relates Andreas Kist. The scientists believe that the observed cerebellar organization is an important trait for neural coding and associative learning: “The modules appeared optimized to organize the information necessary for the principal behaviors of the zebrafish at this age, yet may also allow for the flexibility required to learn new things through experience”, explains Knogler. “I wouldn’t be surprised if other sensory input and the cerebella of other species are organized in a similar way.”.

read more